In the last episode, I've shown you how to debug loading dependencies in Hanami applications by leveraging the power of dry-container.

This time I want to dig deeper into the problem this gem solves with its friends and why it even exists!

important

This episode is the Part 1 of digging into dependency injection in Ruby. Check out Part 2 here! Episode #15 - Dependency injection in Ruby - GOD Level!

Dependency injection with dry-rb gems.

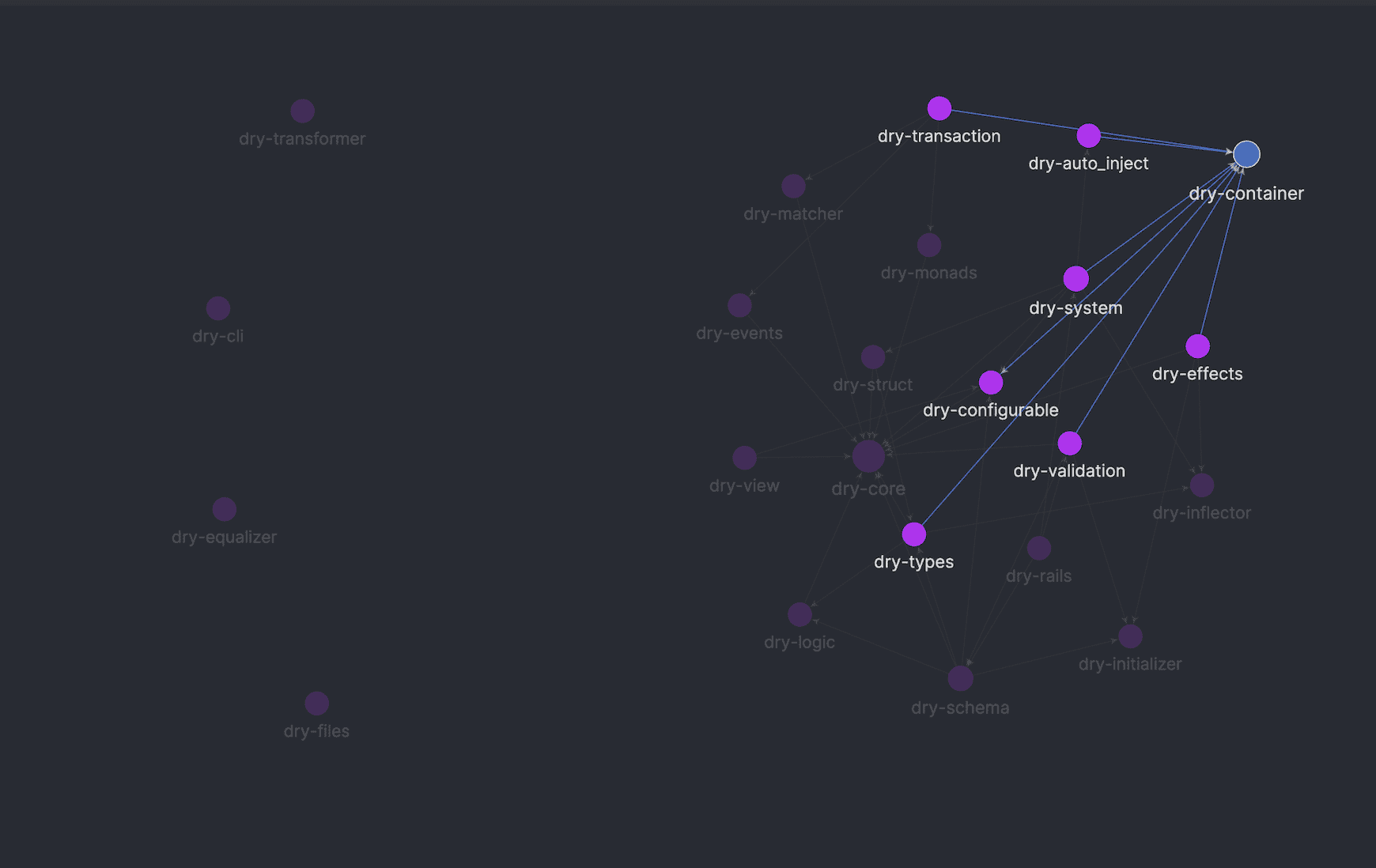

On the dry-rb dependency graph I've created a while ago you may see, that dry_container is actually one of the key gems in the whole dry-rb ecosystem and most cool gems from the dry-rb family use it under the hood.

dry-rb dependency graph

dry-rb dependency graph

But what is so special about it?

Also, why in Hanami applications, except dry-container, you have dry-system and dry-auto_inject gems worked together to handle loading dependencies?

This is exactly what I'll try to talk about today.

Dependency Injection from scratch.

Dependency injection in programming is a technique that allows building your applications around encapsulated, composable objects, that can be easily replaced by something else if needed.

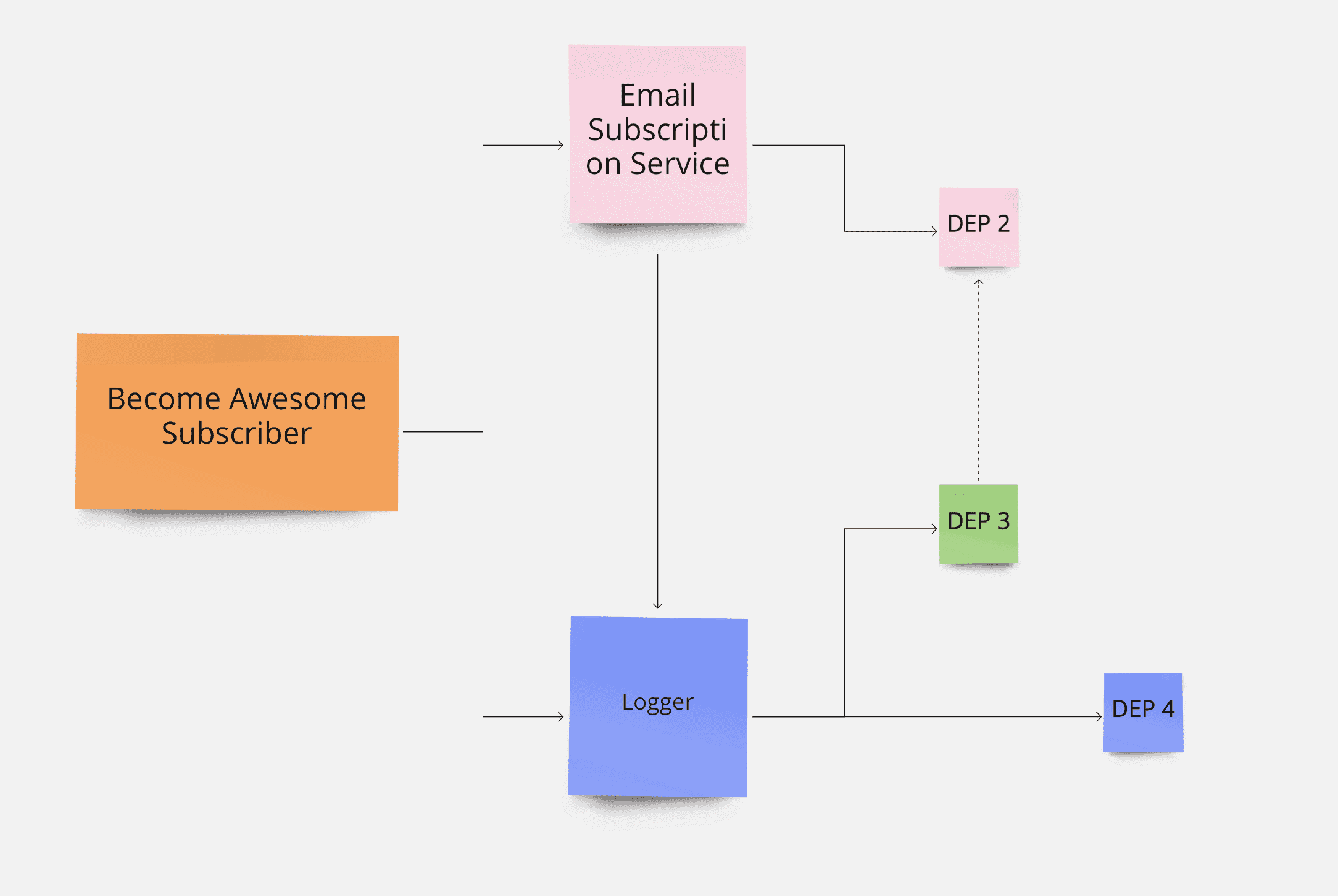

Let's say, there is a Hanami Mastery object, and I want to subscribe to get updates. Hanami Mastery can ask another object to save the subscription while leaving the details of HOW to do it, for that service.

Delegating responsibilities

Delegating responsibilities

This way, as long as the interface is kept the same, we can replace the subscription service with whatever, without a need to do bigger refactoring.

Replacing dependencies

Replacing dependencies

Dependency injection is one of the techniques helping to achieve that.

While I know that the world doesn't need another post about dependency injection in Ruby, I decided to create one anyway, to complement this series and explain the Hanami approach to it.

Dependency injection IS a very simple concept and see the article created by Piotr Solnica which I link in the description, for a numerous list of benefits it provides and how simple it can be.

:::info Not focusing on tests at all! There is a lot of controversy on the web around providing arguments used only for testing purposes and a lot of people talking about DI in Ruby already focused on testing benefits. So I'll skip that part. Somewhat. Maybe just this: dependency injection is extremely useful in testing! :::

In dry-rb family there are three gems dedicated to handling dependency-injection problems:

- dry-container

- dry-auto_inject

- dry-system

And I'll cover each of them separately but it's important to notice, that YOU DON'T need any of those to implement dependency injection in ruby!

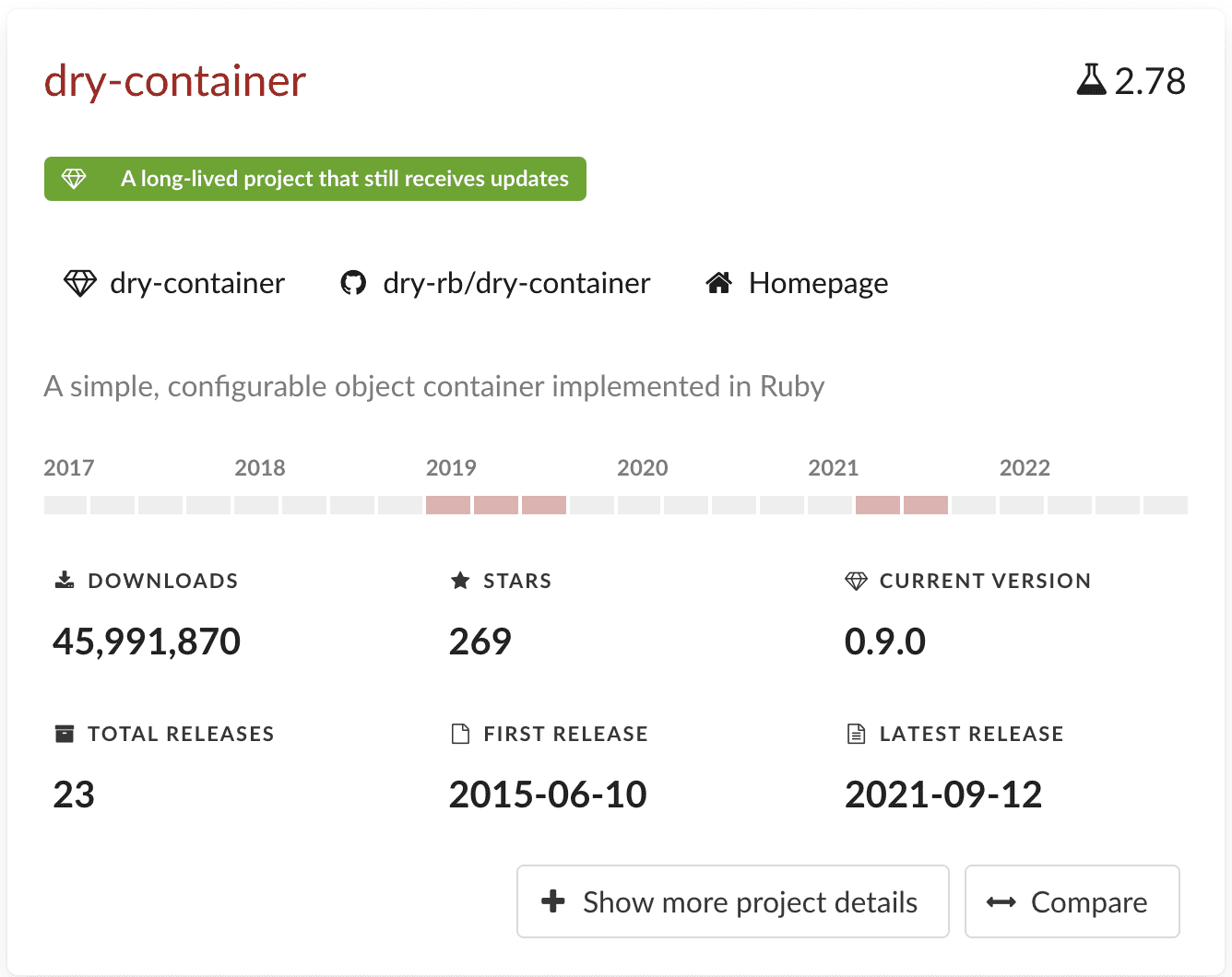

There is a lot of noise around the topic of dependency-injection in Ruby, as DHH somewhat dislikes the idea, but just by looking at how popular some dry libraries are, one may easily disagree with DHH. He likes RSpec neither.

Ruby-Toolbox - Popularity of dry-container

Ruby-Toolbox - Popularity of dry-container

Having that said, here is another example of DI in Ruby.

warning

Examples below will be kept in extremely simple form to show the issues. To grasp the concepts properly though, you need to keep in mind, that applications actually GROW.

Let's say I have this code.

class EmailSubscriptionService

def call(email)

puts "@-_-@"

end

end

class BecomeAwesomeSubscriber

def call(email)

puts "starting subscription..."

EmailSubscriptionService.new.call(email)

puts "subscribed to newsletter!"

end

end

It's just a dummy code snippet, but I want to keep things simple. Imagine though, that your app won't stay this small for a long, or that it's just a tiny part of a larger system.

When I call it I'll get some logs and that's all.

command = BecomeAwesomeSubscriber.new

command.call(email: 'awesome@hanamimastery.subscriber')

# =>

# starting subscription...

# @-_-@

# subscribed to newsletter!

It's easy, but there are a few problems here.

1. Logging logic leaks to the system.

First of all, the logic responsible for generating logs is placed directly in different classes, which makes it hard to refactor. If you'll EVER want to add an additional logging channel like [papertrail] or even own S3 bucket, you'll have hell in replacing all log calls in your application.

I won't replace my logger!

Yeah, if you won't, probably you don't write tests....

You can easily solve it by adding a Logger class that hides this logic and provides own interface to generate and send logs.

class Logger

def call(msg)

puts msg

end

end

class EmailSubscriptionService

def call(email)

logger = Logger.new

logger.call("@-_-@")

end

end

class BecomeAwesomeSubscriber

def call(**args)

logger = Logger.new

logger.call("starting subscription...")

EmailSubscriptionService.new.call(args[:email])

logger.call("subscribed to newsletter!")

end

end

This approach hides the logging logic somewhat, but it's far from perfection. When I call my services multiple times, it'll instantiate my Logger each time and it doesn't really solve the problem of replacing the logger easily in whole classes.

2. Hard to refactor

Nobody wants to wonder in how many places in the class itself I need to replace the Logger class when a new logging mechanism is introduced.

As logger is a dependency, we can move the initialization into the initialize methods of the classes using it, which will keep instantiation logic in one place.

class EmailSubscriptionService

attr_reader :logger

def initialize

@logger = Logger.new

end

def call(email)

logger.call("@-_-@")

end

end

class BecomeAwesomeSubscriber

attr_reader :logger, :service

def initialize

@logger = Logger.new

@service = EmailSubscriptionService.new

end

def call(email)

logger.call("starting subscription...")

service.call(email)

logger.call("subscribed to newsletter!")

end

end

Please notice that I identified that EmailSubscriptionService is also a dependency of my BecomeAwesomeSubscriber command and extracted it too.

Now we are one step closer to the composable code and our refactoring would be a bit simpler. Now I only need to look at initialize methods if needed and replace Logger there. However, it's still a lot of places to check, in case you want to do this change.

3. Memory optimizations

When I'll just instantiate the BecomeAwesomeSubscriber service object, I'll end up with 2 instances of Logger class, both completely identical!

And every time sth will use my objects, new loggers will be created.

require 'objspace'

ObjectSpace.each_object(Logger).count # => 0

cmd = BecomeAwesomeSubscriber.new

ObjectSpace.each_object(Logger).count # => 2

srv = EmailSubscriptionService.new

ObjectSpace.each_object(Logger).count # => 3

I know how it looks.

What's the point of it? - you may ask. - Two or three more objects? Who cares?

Well, I DO CARE.

When you start working on big projects, memory optimizations actually start to matter. This is an extremely small example, but if your code is not optimized in the framework you use and across the whole project, you may easily end up with thousands or tens of thousands of unnecessary objects generated all the time everywhere.

This is just one reason **why Hanami is so much more memory-optimized in comparison to Rails!

So in our example, we may do better though by allowing us to INJECT our dependencies.

class Logger

def call(msg)

puts msg

end

end

class EmailSubscriptionService

attr_reader :logger

def initialize(logger: Logger.new)

@logger = logger

end

def call(email)

logger.call("@-_-@")

end

end

class BecomeAwesomeSubscriber

attr_reader :logger, :service

def initialize(logger: Logger.new, service: EmailSubscriptionService.new)

@logger = logger

@service = service

end

def call(email)

logger.call("starting subscription...")

service.call(email)

logger.call("subscribed to newsletter!")

end

end

With this, we can finally solve all our problems!

require 'objspace'

logger = Logger.new

ObjectSpace.each_object(Logger).count # => 1

cmd = BecomeAwesomeSubscriber.new(logger: logger)

ObjectSpace.each_object(Logger).count # => 2

srv = EmailSubscriptionService.new(logger: logger)

ObjectSpace.each_object(Logger).count # => 2

Wait, what?

cmd = BecomeAwesomeSubscriber.new(logger: logger)

ObjectSpace.each_object(Logger).count # => 3

cmd = BecomeAwesomeSubscriber.new(logger: logger)

ObjectSpace.each_object(Logger).count # => 4

I reduced the number of objects generated, but there is still a flaw in the example!

As I don't pass EmailSubscriptionService to the BecomeAwesomeSubscriber, and it also uses Logger, new Logger objects are still regenerated!

It's easy to fix though by a little tweak to the code calling my example.

require 'objspace'

logger = Logger.new

ObjectSpace.each_object(Logger).count # => 1

srv = EmailSubscriptionService.new(logger: logger)

ObjectSpace.each_object(Logger).count # => 1

cmd = BecomeAwesomeSubscriber.new(logger: logger, service: srv)

ObjectSpace.each_object(Logger).count # => 1

I did this mistake intentionally to present how easy it is to overlook objects initialization and miss one dependency if you do things manually, but it's already fine.

With this, we've implemented the complete dependency injection mechanism.

Now you can easily test your classes on the unit-level by just injecting dependencies when needed and use mock objects freely. Different parts of your systems can use different loggers and much fewer objects are created across the system.

But... Long names....

When the application grows though, you start to see a bit more problems though. Naming Problems in particular.

If I have a project supporting multiple contexts, the number of namespaces in my system grows very quickly.

You may keep your file namespaces flat, but You can't avoid long names at all. Here are few examples:

logger = MyApp::Utils::Loggers::IOLogger.new

srv = MyApp::Client::Services::Subscriptions::EmailSubscription.new(logger: logger)

# vs

srv = MyApp::ClientEmailSubscriptionService.new(logger: logger)

If you ask me... I hate flat file structures.

Let me create my example classes with a bit more structure in mind then.

# lib/my_app/utils/loggers/io_logger.rb

module MyApp

module Utils

module Loggers

class IOLogger

def call(msg)

puts msg

end

end

end

end

end

# lib/my_app/utils/services/subscriptions/email_subscription.rb

module MyApp

module Utils

module Services

module Subscriptions

class EmailSubscription

attr_reader :logger

def initialize(logger: MyApp::Utils::Loggers::IOLogger.new)

@logger = logger

end

def call(email)

logger.call("@-_-@")

end

end

end

end

end

end

# slices/blog/commands/become_awesome_subscriber

module Blog

module Commands

class BecomeAwesomeSubscriber

attr_reader :logger, :service

def initialize(

logger: MyApp::Utils::Loggers::IOLogger.new,

service: MyApp::Utils::Services::Subscriptions::EmailSubscription.new

)

@logger = logger

@service = service

end

def call(email)

logger.call("starting subscription...")

service.call(email)

logger.call("subscribed to newsletter!")

end

end

end

end

You can feel the pain, can't you?

This is a bit frustrating, to define manually all those dependencies over, and over again, and this actually can become hard to maintain very quickly.

And this is where dry-container comes in with help.

Dry-container in action

In all of the examples above, each of the class needed to know EXACTLY how to resolve all dependencies of all other dependencies or we could end up with multiple instances of the same classes being created all over the place.

We either need to set defaults, which makes our init methods unclear very quickly, or we will end up with troubles figuring out what the class accepts.

The idea behind dry-container is to extract this knowledge into one place. Let me create the container.

# system/container.rb

require 'dry-container'

# define the container

class Container

extend Dry::Container::Mixin

end

# boot.rb

require_relative './system/container.rb'

# register our dependencies

Container.register('my_app.utils.logger', MyApp::Utils::Loggers::IOLogger.new)

Container.register(

'services.email_subscription',

MyApp::Utils::Services::Subscriptions::EmailSubscription.new(

logger: Container['logger']

)

)

Container.register(

'commands.become_awesome_subscriber',

MyApp::Blog::Commands::BecomeAwesomeSubscriber.new(

logger: Container['logger']

service: Container['services.email_subscription']

)

)

With this we can completely get rid of any default arguments in all our classes, because we can now resolve all our dependencies during boot-time and always use already resolved objects!

# lib/my_app/utils/services/email_subscription.rb

attr_reader :logger

def initialize(logger:)

@logger = logger

end

# slices/blog/commands/become_awesome_subscriber.rb

attr_reader :logger, :service

def initialize(logger:, service:)

@logger = logger

@service = service

end

Then using this would be as simple, as just calling the proper container keys.

cmd = Container['blog.commands.become_awesome_subscriber']

cmd.call(email: 'awesomesubscriber@hanami.mastery')

If I'll now want to do the same check as before with counting objects, I'll get no issues whatsoever.

require 'objspace'

cmd = Container['blog.commands.become_awesome_subscriber']

cmd.call(email: 'awesomesubscriber@hanami.mastery')

logger_class = MyApp::Utils::Loggers::IOLogger

ObjectSpace.each_object(logger_class).count # => 1

Container['blog.commands.become_awesome_subscriber']

Container['blog.commands.become_awesome_subscriber']

ObjectSpace.each_object(logger_class).count # => 1

Resolving ALL dependencies

The usage is much more simple now, but imagine this for larger applications. When I want to use anything, we don't need to resolve all dependencies manually, but just rely on the container to do it properly.

With a single line of code, our Container can resolve whole trees of dependencies without any overhead from our side.

On top of that, while dry-container allows us to lazy-load dependencies on Runtime, just when they're needed, we can also load them all at once on boot time, which may be useful for production environments!

# boot.rb

# ...

Container.finalize!

Keep in mind, that this single line of code actually resolves a whole tree of dependencies in one place, and you never need to worry about them in your app.

dry-container - resolving dependency trees)

dry-container - resolving dependency trees)

Browsing all dependencies in the system

Also, you may easily get an overview of everything that is happening in your system!

Container.keys

# => [

# 'logger',

# 'services.email_subscription',

# 'commands.become_awesome_subscriber

# ]

I described it in details in HME013 so feel free to check it out!

Summary

Dependency injection is awesome, but comes with own headaches.

dry-container streamlines resolving dependency trees and keeps our app memory-optimized and fast by loading only what's necessary or everything at once if we want.

What I described above is only a scratch benefits dry-container provides. Some other cool things associated with it are:

- it's thread-safe

- you can define multiple containers for multiple parts of the system.

- it's priceless in testing - yeah, I know I am supposed to not talk about it.

However, it's still only one gem. So what are the others for?

In the next episode I'll showcase the dry-auto_inject and dry-system gems, stay tuned for that!

That's all for today, I hope you enjoyed this episode and you'll give dry-container a try.

Become an awesome subscriber!

If you want to see more content in this fashion, Subscribe to my YT channel, Newsletter and follow me on Twitter!

Thanks

I want to especially thank my recent sponsors,

- Andrzej Krzywda,

- Sebastjan Hribar,

- and Useo

for supporting this project, I really apreciate it!

By helping me with a few dollars per month creating this content, you are helping the open-source developers and maintainers to create amazing software for you!

And remember, if you want to support my work even without money involved, the best you can do is to like, share and comment on my episodes and discussions threads. Help me add value to the Open-Source community!

Add your suggestion to our discussion panel!

I'll gladly cover them in the future episodes! Thank you!