Recently I've written an article, where I've told about the decision process behind my attempt to replace Rails with Hanami in our microservices ecosystem and why I decided not to do it just yet.

important

Please keep in mind that this statement was made before even Hanami 2-alpha versions had been officially released.

The important part was, that rewriting my Hanami application to Rails took me less than a day - and I was able to do so, because of how I and my team tend to structure code in our web applications for the recent years.

Then I've gone through this great article about using Service Objects in Rails applications and It plucked my heartstring. At first, I thought: Another article about Service objects, which I personally HATE.

But almost instantly, a second thought came to my mind, revealing, that I am actually a super fan of service objects. I just only don't name them this way, I use more abstractions and extract dependencies out for better clarity.

So in this episode, I'll show you my version of service objects that allowed me to replace one ruby web framework with another in a complete service in less than a day.

:::important Disclaimer. This was a very small API-only service. :::

In the next couple of minutes, I'll go through refactoring the onboarding endpoint to the structure we use in our microservices. Maybe it'll inspire you to improve your codebases and If it will, please send me your ideas so I can learn from!

Enjoy!

Why do we need service objects?

I have here a simple Rails API application, with a single endpoint, that allows me to register only a single user. I did simplify it for this video but wanted to implement a few hidden functionalities, so it is enough to visualize the benefits of the refactoring.

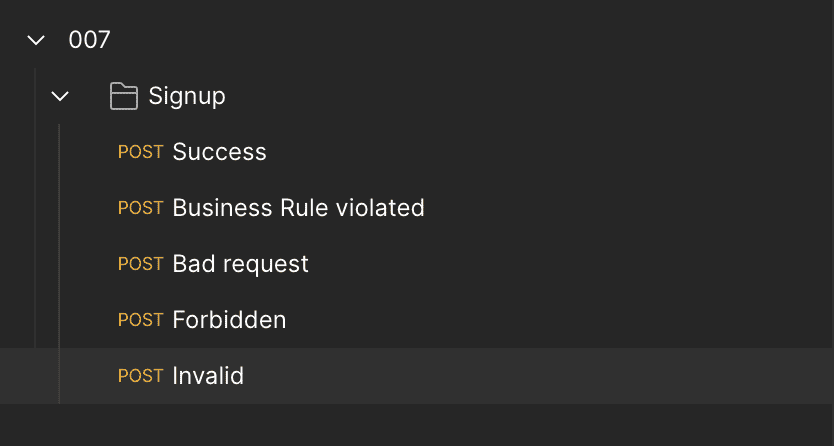

List of onboarding error responses

List of onboarding error responses

tip

Just please keep in mind, that the more complex the problem your application solves is, and the bigger your project grows, this technique will give you more and more benefits.

I've tested it in small microservices but also in big monolithic applications with hundreds of endpoints available.

Rails controllers do too much

So I have this single endpoint that creates a user and you may think it's the only thing it does but is it really?

It returns an error where another user had already been registered, a different error when the request body is wrongly formatted, one more when there is no authorization header, and finally the validation errors when user validation fails.

If I'll visit the controller, you will see, that even for this single action there is quite a lot happening.

# app/controllers/onboarding/registrations_controller.rb

module Onboarding

class RegistrationsController < ApplicationController

before_action :authorize!

AuthorizationError = Class.new(StandardError)

rescue_from AuthorizationError, with: -> { head :forbidden }

rescue_from ActionController::ParameterMissing, with: -> { head :bad_request }

def create

user = User.new(user_params)

if user.valid?

if User.count > 0

message = 'too many subscriptions! Try again later'

return render json: { errors: message }, status: 418

end

user.save

head :created

else

render json: { errors: user.errors }, status: :unprocessable_entity

end

end

private

def user_params

params.require(:user).permit(:name, :email)

end

def authorize!

token = request.headers['Authorization'].to_s.gsub('Bearer ', '')

raise AuthorizationError if token.blank?

end

end

end

At the very top, you have the authorization check, which I've just implemented as a placeholder for this showcase, checking if the authorization header is present. I've written a complete tests coverage for this project to refactor safely, and it had been caught by one test example.

Then when there are specific errors risen, I'm rescuing from them calling proper error rendering methods.

Still, this single controller action does several things and there are some issues hard to be seen and tough to debug.

And this is a super simple one.

My experience from big rails projects shows that one can never underestimate, how big rails controllers may become.

Hidden issues in standard Rails applications

Let me go through some of the issues hidden here.

Unnecessary DB requests

You can see, that it first authorizes the request. It's not ideal, because it happens before params deserialization. This usually means, fetching objects from the database, like the OAuth application, or current user, which may result in unnecessary DB queries.

Imagine big CanCanCan Ability class, and You'll immediately get an idea what I'm talking about.

Conditional validations

Then we have the validation check, rendering validation errors in case of failure. Here is another common problem hidden. The user may be valid for creation, but to update the user, you could need different validation rules.

In this case, you'll end up with conditional validations which are very hard to be tracked.

API versioning and backward compatibility

Also when your application supports multiple API versions, it may be possible, that in the older API version your user was valid, but then you had added more validation rules to the user and the new API is not backward compatible.

API versioning, when we have validations stored in global Active Record models, is very hard to maintain, and this is the main reason I'm avoiding storing validation logic inside of the models.

Business logic in the controller

Then, finally, we have a business validation rule that prevents our action to succeed. It's not about validating the input.

The request body is completely valid and the client has an access to perform the request, but at the current state of the application, this action is not allowed due to the business condition.

These kinds of checks are something I often see in rails controllers or models, but I love the approach coming from Domain Driven Development, where the Business logic is aggregated in a completely separated object.

So what our controller does?

If we take all above and sum them up, it'll be clear that our controller

- Deserializes the input

- Authorizes the request

- Validates the params

- Checks business conditions

- Performs the action (updates the application state)

- Serializes the response

Each of these steps can potentially be a bit complicated, like validating the request parameters, or checking if the business rules allow for given action to be performed in the current application state.

It makes TOTAL SENSE then to not keep it all in the controllers, right?

However, in most Rails applications all those steps tend to be squeezed between the Model and Controller without too much thought behind managing business processes.

If you'll add 10 additional actions to the single user model, you'll easily end up with a big mess.

So, writing service objects for each and every action in your controller is pretty useful.

Refactoring the controller action

Now let me refactor this code to make it more straightforward, more scalable, and more reliable.

I'll use tree gems to do that.

1. Dry-Monads

To easily create objects which list several steps to perform, and better handle errors, I'll use Dry-Monads.

With this gem, I'll be able to ensure, that All my objects always return the same type of objects, either Success or Failure, which can be easily caught, compared, and processed later.

2. Dry-Matcher

Dry-Matcher is a pattern matching for Ruby that puts error handling to the next level. It has built-in integration with dry-monads, so It's a natural candidate to be used as a comparison engine for different failure objects.

3. Dry-Validation

Finally, Dry::Validation is the best validation engine I know. I use it in all my projects for years already, to extract my validation rules out of Active Record objects.

While I'll go through the implementation pretty fast in this episode if you're interested in deeper dive into any of those gems, let me know using #suggestion - and you can consider sponsoring me on Github to get a bigger impact on future episodes content.

Action object

Going back to the refactoring. First of all, I'll not start from the ServiceObject.

A service is an object that performs a single Business Process, so it should not be concerned about any of this authorization or validation stuff. It makes sense then to not call it directly from the controller.

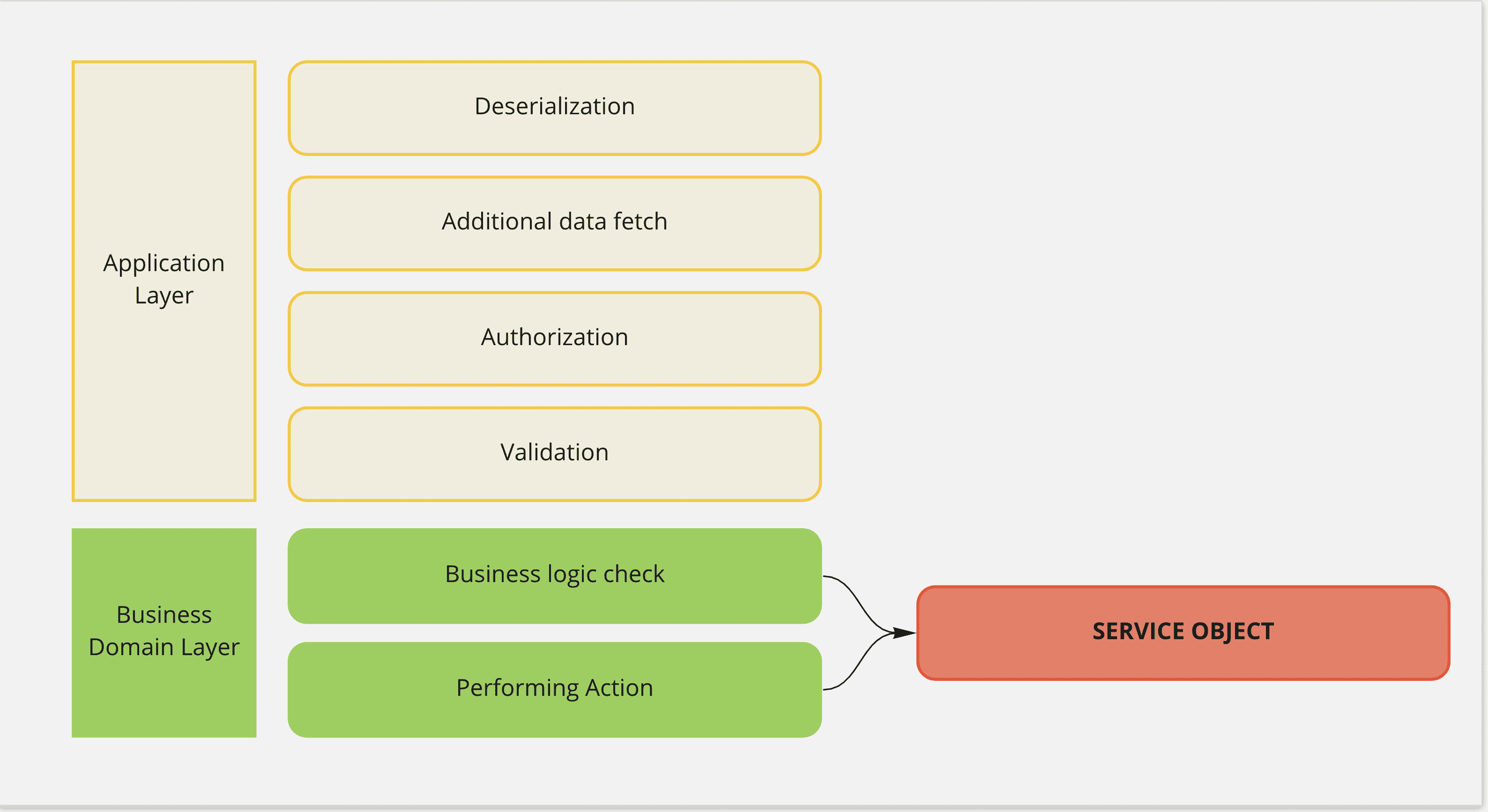

Service Object responsibility

Service Object responsibility

This is why when I implement my Rails endpoints, I'm always starting from creating the endpoint action object, where I list all the steps that are required to perform the single action.

It accepts a rack request and returns the serializable response. Writing your controller actions in the way they're Rack-Compatible is the first step to create truly framework-agnostic web applications.

# /lib/onboarding/endpoints/create_user/action.rb

require 'dry/monads'

require 'dry/matcher/result_matcher'

module Onboarding

module Endpoints

module CreateUser

class Action

include Dry::Monads[:do, :result]

include Dry::Matcher.for(:call, with: Dry::Matcher::ResultMatcher)

def call(request)

# Steps to be listed here

Success(status: :created)

end

end

end

end

end

It'll contain a single call method as the only interaction point. I try to make all my projects callable, so it's easier to maintain communication between them.

Then I'll include the result monad so I can access Success and Failure objects directly, without prepending them with Dry::Monads - and enable the do notation.

Now let's list the steps.

# /lib/onboarding/endpoints/create_user/action.rb

def call(request)

model, auth = yield deserializer.call(request)

yield authorizer.call(model, auth)

res = yield validator.call(model.to_h)

yield create_user.call(res.to_h)

Success(status: :created)

end

First I need to deserialize the request, getting the parameters and the authorization data. In this case, authorization will be just a token for simplicity.

Then I want to check the authorization logic - only after validating the format of the request body.

If this one succeeds, I call the validator to run validation rules.

Only in case the validation passes, I call the CreateUser service object, to actually try performing the business process action.

This way, my CreateUser service can be easily called from other places of the system, like background workers, or the developer console, where I don't need for example authorization check.

Each of those steps is an endpoints dependency. The action object is only concerned about what to call, and in which order, but the detailed logic is hidden in separate step classes.

# /lib/onboarding/endpoints/create_user/action.rb

require 'dry/monads'

require 'dry/matcher/result_matcher'

module Onboarding

module Endpoints

module CreateUser

class Action

include Dry::Monads[:do, :result]

include Dry::Matcher.for(:call, with: Dry::Matcher::ResultMatcher)

def call(request)

model, auth = yield deserializer.call(request)

yield authorizer.call(model, auth)

res = yield validator.call(model.to_h)

yield create_user.call(res.to_h)

Success(status: :created)

end

private

attr_reader :deserializer, :authorizer, :validator, :create_user

def initialize

@authorizer = Authorizer.new

@deserializer = Deserializer.new

@validator = Validator.new

@create_user = Operations::CreateUser.new

end

end

end

end

end

Let me implement them quickly.

Deserializer

The first step is a deserializer. It is supposed to ensure that params and headers are in a valid format.

The call method also accepts the rack request and returns either Success or Failure value.

First I need to get the params, then validate the format using deserialize method. It does pretty much the same that the controller did, but it catches the ParameterMissing error and returns the Failure object instead.

Then I get the authorization data - just for simplicity I just extract the token from headers. You may replace it with JWT token decoding, or whatever else you use in your application.

And at the end, return the Success monad.

# /lib/onboarding/endpoints/create_user/deserializer.rb

require 'dry/monads/result'

module Onboarding

module Endpoints

module CreateUser

class Deserializer

include Dry::Monads[:do, :result, :try]

def call(request)

params = ActionController::Parameters.new(request.params)

model = yield deserialize(params)

auth = yield fetch_token(request)

Success([model, auth])

end

private

def deserialize(params)

res = Try[ActionController::ParameterMissing] do

params.require(:user).permit(:name, :email)

end

res.error? ? Failure(:deserialize) : res

end

def fetch_token(request)

token = request.headers['Authorization'].to_s

Success(token.gsub('Bearer ', ''))

end

end

end

end

end

Authorizer

The second step is to authorize the action using the given parameters and authorization data. It may happen, that in-between-step will be required to fetch additional data for the authorizer to proceed, and you can imagine, how easy it would be to add such here.

My simple authorizer will just check if the token extracted from the header is present - but you may imagine that quite complex authorization rules may be listed here.

Again, It returns either Success or failure.

# /lib/onboarding/endpoints/create_user/authorizer.rb

require 'dry/monads/result'

module Onboarding

module Endpoints

module CreateUser

class Authorizer

include Dry::Monads[:result]

def call(_model, auth)

auth.length.zero? ? Failure(:authorize) : Success()

end

end

end

end

end

I hope you start seeing the pattern here. Because of the fact that all my objects return always the Result monad, I am free to handle all of them in the exactly same way.

Validator

The third step is the actual validation. In the user object, I have the presence validation for name and email, and also the uniqueness check for the email field.

# /app/models/user.rb

class User < ApplicationRecord

validates :email, uniqueness: true

validates :name, :email, presence: { message: 'must be filled' }

# after_create :send_notification email

end

Let's replicate that using dry-validation here.

At the very top of my validator, I'm loading the monads extensions, to make my validators compatible with the Success and Failure objects I return in my other steps.

# /lib/onboarding/endpoints/create_user/validator.rb

require 'dry/validation'

Dry::Validation.load_extensions(:monads)

module Onboarding

module Endpoints

module CreateUser

class Validator < Dry::Validation::Contract

# rules go here

end

end

end

end

First, let's define the basic validation rules. They will be already more powerful due to the built-in type checking.

First I need the name to be required and present, with the type of string. Then I repeat the same for email...

... and I wrap those rules into the params coercion block, which does the basic value transformation at the beginning. If you're interested in details about it, I strongly recommend you to visit the dry-validation's documentation page where this is explained deeply.

# /lib/onboarding/endpoints/create_user/validator.rb

...

class Validator < Dry::Validation::Contract

params do

required(:name).filled(:string)

required(:email).filled(:string)

end

end

...

Now Let's write the uniqueness validation for email. This will only be checked if the basic validations passed.

I add a custom rule for email, which returns a failure for this attribute key with the given message if the user with this email already exists in our database.

However, I don't want to make my validator coupled to User class, so I inject it as a repository using the option feature.

# /lib/onboarding/endpoints/create_user/validator.rb

...

class Validator < Dry::Validation::Contract

option :repository

params do

required(:name).filled(:string)

required(:email).filled(:string)

end

rule(:email) do

key.failure('must be unique') if repository.exists?(email: value)

end

end

...

Then let me go back to the action, and during the initialization of the validator specify that the repository that should be used by the validator is a User class.

# /lib/onboarding/endpoints/create_user/action.rb

@validator = Validator.new(repository: User)

This makes it extremely easy to test in encapsulation, as I can just inject anything to my validator that responds to the exists? method - so there is no coupling to rails or active record objects.

Service Object

Finally, I call the CreateUser service object (or interactor) with the value that is returned from my validator. At this point, I am hundred percent sure that I'm always working with the valid input parameters, correct types, and values so I can easily skip validation, or raise unexpected errors if such a situation happens.

Different names for service objects

You may notice that I tend to call my service objects - operations, the same I did for validators instead of contracts - but that's irrelevant. Call them however you wish, just be consistent.

Other names you may see on the web:

- interactors

- operations

- service objects

Let me create the service object quickly.

Again, the object has a single call method. It fails if there is already a user registered, then creates a user and returns success otherwise.

You can easily extend it to schedule some notification emails or do other fancy updates, but the core thing here is that none of this stuff is application-related, but rather performs the business process.

# /lib/onboarding/operations/create_user.rb

require 'dry-monads'

module Onboarding

module Operations

class CreateUser

include Dry::Monads[:result, :try]

def call(args)

failure_message = 'too many subscriptions! Try again later'

return fail!(failure_message) if User.count > 0

User.create!(args)

# schedule_email(args)

Success()

end

private

def fail!(message)

Failure[:teapot, message: message]

end

end

end

end

With this, our endpoint is pretty much done.

The call_action method

Finally, let's go back to our controller and clean it up.

I can pretty much remove everything from here, replacing the method with only a single line, calling the given action object.

# /app/controllers/onboarding/registrations_controller.rb

module Onboarding

class RegistrationsController < ApplicationController

def create

call_action(create_user)

end

private

def create_user

Endpoints::CreateUser::Action.new

end

end

end

The call_action method takes care of the error handling and this is where we make use of dry-matcher integration.

it accepts the given action and calls it with the rack request. Then in case, the action is successful, it renders an empty body with the status got from the result.

# /app/controllers/application_controller.rb

class ApplicationController < ActionController::API

private

def call_action(action)

action.call(request) do |result|

result.success { |status:| head status }

result.failure(:deserialize) { head :bad_request }

result.failure(:authorize) { head :forbidden }

result.failure(Dry::Validation::Result) do |res|

render json: { errors: res.errors.to_h }, status: :unprocessable_entity

end

result.failure(:teapot) do |message:|

render json: { errors: message }, status: 418

end

result.failure { head :server_error }

end

end

end

in case it's a deserialization issue, it returns the bad request HTTP status, and respectively for authorization failure, the forbidden error is returned.

Where a failure is a validation object then we can render the validation errors with unprocessable_entity status code,

and when business logic fails, we can return something else, like a teapot with a detailed message.

Finally, if there is another type of failure returned, we can return the 500 HTTP status code.

The refactoring completed!

Summary

There are of course pros and cons of this approach.

Is this code easier to read? I would say so, but it requires more jumping between files.

- It's way easier to test, so you can practice complete Test-Driven development without an effort.

- It's more scalable

- less error-prone.

It allows me to update rails projects easily, or even replace one web framework with another in no time.

However, the drawback is that more actual code needs to be written.

I've designed this years ago for our Rails applications, and I was AMAZED, when I've discovered, that Hanami actually evangelizes a very similar programming style and conventions.

If you consider trying Hanami after years of working with Rails, you'll meet more such programming styles, where dependencies are injected from outside, and the single responsibility is encouraged for your objects.

To summarize

don't be afraid of putting more abstractions to your systems. If service objects are supposed to only handle business processes, maybe calling them directly from the controller is not the best approach.

Instead of naming everything service, I name objects based on what they actually are, and this reduced the amount of code that needed to be refactored when I needed to change frameworks, or more often when I need to update the Rails or Hanami in our projects.

Here are some ideas for naming ruby objects in web applications.

Different abstraction names examples

Different abstraction names examples

I hope you've enjoyed this episode and as always I'd like to say thanks to my Github sponsors, I appreciate the support as it allows me to create better content and it speeds up the development of the Hanami web framework.

If you enjoyed this episode and want to see more content in this fashion, Subscribe to this YT channel** and follow me on twitter! As always, all links you can find the description of the video or in the https://hanamimastery.com.

Thanks

Special thanks to:

- Mae Mu - For a great cover photo

- Benjamin Klotz For being my Github sponsor of High Five! supporters tier!

Add your suggestion to our discussion panel!

I'll gladly cover them in the future episodes! Thank you!